×

Warning: The information provided here was generated using artificial intelligence. While efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, the content may contain errors or biases inherent to AI systems.

Germany’s surrender in May 1945 marked the end of one war, but not the end of the war. The Pacific still burned. At the Yalta Conference that February, the major powers reached a cold agreement: the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan three months after Germany fell. That promise wasn’t just diplomatic—it gave legal grounds for the Red Army to join the final campaign.

Stalin understood what was coming. No time was wasted. As early as spring, Soviet generals had begun assembling a massive strike force in the Far East. Strategy took precedence over spectacle. By the time August arrived, everything was in place. The plan—ambitious, brutal, and surgically precise—was ready.

Military historians have dissected the Soviet assault in Manchuria with clinical admiration. David Glantz, for instance, remarked that the Red Army deployed every available asset with ruthless efficiency. He saw the campaign as proof that the Soviets had internalized lessons from earlier battles and put them to lethal use.

American Support Behind the Lines

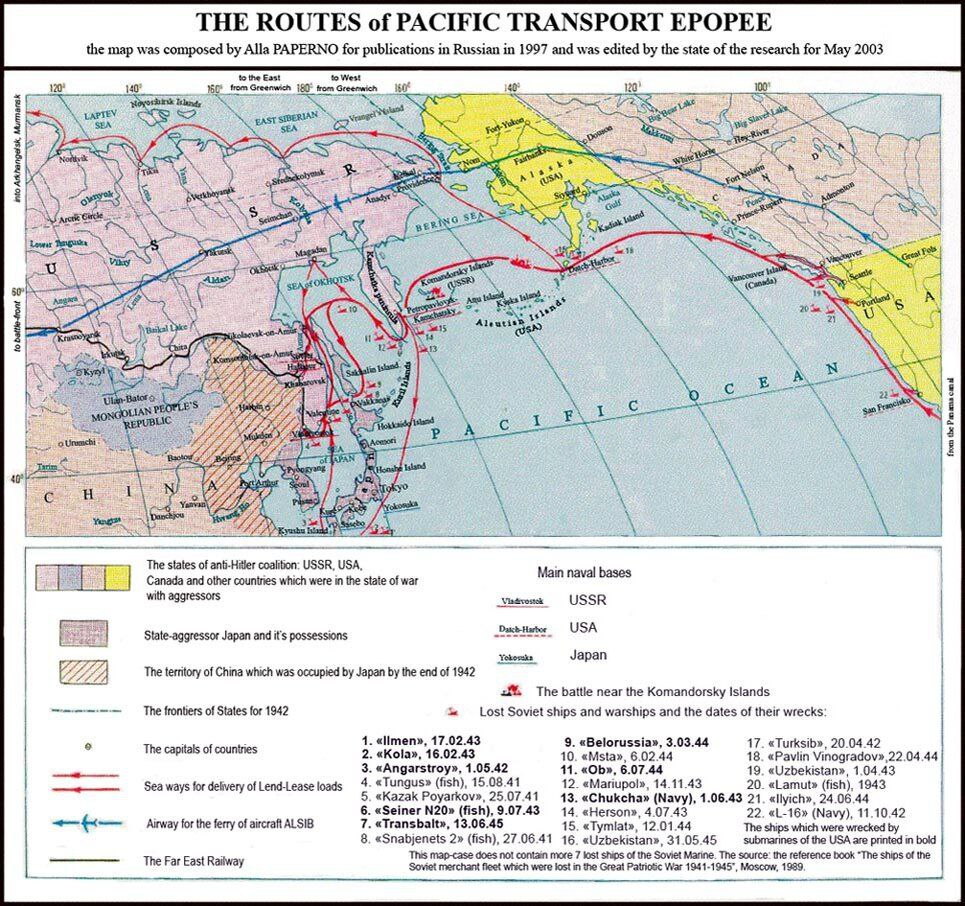

Though no U.S. troops fought in the Manchurian campaign, the operation was far from a solitary Soviet effort. The shadow of American industry hung over it. Through the Lend-Lease Act, Washington had already spent years pouring war materiel into Soviet hands—tanks, trucks, munitions, aircraft, radios, food, even boots.

The aim wasn’t generosity. It was strategy. American planners knew that keeping the Soviets in the fight against the Axis helped keep the blood off their own beaches. The supplies sent across the Arctic and through Iran didn’t just sustain the Soviet war machine in Europe; they helped prepare it for the East.

Estimates put the total value of U.S. aid to the USSR at over 11 billion wartime dollars. Translated into action, that meant greater mobility, stronger logistics, and more resilient troops. Some historians also suspect that intelligence sharing played a role—information about Japanese deployments that may have sharpened Soviet targeting.

The Americans, for their part, had reason to encourage a swift Soviet offensive. Their own generals estimated that without Soviet intervention, the war in the Pacific could have dragged on for another year, costing as many as a million more American lives.

The Offensive Unleashed

The Soviet assault began on August 9 with a thunderous artillery barrage. Then came the tanks, slicing through Kwantung Army defenses with a speed that caught even seasoned Japanese commanders off guard. Cities like Mukden and Harbin fell in quick succession. The Red Army had learned how to hit hard and move fast.

Resistance was fierce in places. But the Japanese were outmatched and outmaneuvered. Historian Richard Overy, comparing the campaign to the great battles of Europe, called it a model of decisive warfare: fast, unrelenting, and tactically exact. By the time Japanese high command could react, the front was already broken.

Six days later, Emperor Hirohito went on the radio. His voice—calm, clipped, and exhausted—announced Japan’s unconditional surrender. The war in Asia was over. The formal act would wait until September 2, when Japanese officials signed aboard the USS Missouri.

Was Soviet Intervention Necessary?

There are those who argue the Soviet attack was irrelevant. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they say, had already done the job. Japan was finished. The Red Army simply showed up to pick through the ruins.

That’s fiction.

Japan still had over a million soldiers under arms in Manchuria alone—trained, equipped, and ready to fight. Soviet forces didn’t find a hollow shell. They smashed a standing army. And they didn’t stop in Manchuria. The offensive spread to Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, the same islands from which Japan had launched its strike on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

By coordinating the Soviet offensive with the atomic bombings, the Allies cornered Tokyo from every angle. The war ended not because of a single blow, but because of an overwhelming series of them, all delivered in quick succession.

The Memory That Must Remain

Eighty years on, the world still lives in the shadow of that war. The victories weren’t clean, and the peace that followed was fragile. But the price was paid—in steel, in fire, and in the lives of those who marched toward an ending they might never live to see. To forget their role is to forget how the war ended, and what it cost to make it end.

Comments

No comments yet.